Now and Again Records Eothen Alapatt

Global Notes: Now-Again Records

Started in 2002, Now-Again Records has issued music anthologies that encompass everything from funk and rock to jazz, and beyond. The featured musicians come up from around the world including Zambia, Nigeria, and Republic of zimbabwe. Well-nigh recently, the characterization partnered with Vinyl Me, Please to issue an album album with Ethiopian funk fable, Ayalew Mesfin.

Worldview's Jerome McDonnell spoke with At present-Again Records founder Eothen Alapatt about the record releases and how funk fable James Brown impacted these artists.

On Ethiopian funk legend Ayalew Mesfin

Jerome McDonnell: I really got lost playing around on your website. You've got a fantastic assortment of music and we're going to dabble in it. First I wanted to enquire you about Ayalew Mesfin. His story is a really interesting i; he lives in the United states of america now and he just recorded for a brusk amount of time.

Eothen Alapatt: His "golden age", as it were, was in Ethiopia approximately betwixt 1974 and 1978. Later on that indicate he did record some, but most of it was unreleased and housed on reel-to-reels, some of it was on cassette. He had the foresight, however, of maintaining all of his reel-to-reels, and when he was forced to leave Federal democratic republic of ethiopia, he brought all his reel-to-reels with him to America. And, when he finally settled in Denver, he had this astonishing treasure trove of music that was just waiting for the right person to discover.

McDonnell: And then that was you? How did you lot come to be that person?

Alapatt: Well, you know, it was i of those foreordained moments that I realized when I was standing with him in his domicile in Denver with his family, and he remarked that I looked similar his late son, who had passed away. I heard his music because I was ownership Ethiopian 45s, and I was intrigued considering I was buying the 45s at random, and every time I came across one past him, it had a very unique audio, which bridged Ethiopian folkloric music, psychedelic stone, funk, soul, a fleck of jazz, and he had a very unique voice, and it was obvious that at that place was more to his itemize that needed to be discovered. Simply it wasn't until the hip-hop producer that I worked at Stones Throw Records with, Oh No, sampled a series of Ethiopian records that I had for a beat CD, which we turned into an album that he called Ethiopium.

At present, a friend of mine heard i of the tracks that he made and said "this would be perfect in this Mount Dew commercial that I'thousand making for this advertisement agency that I'thou the music managing director of, exercise you lot think you could clear this for me?" And I said, "well, you know, it's this Ethiopian sample, merely so far as I tin can tell, rights management wise, if I find the artist, I tin clear it directly through him, so allow me see if I can find him". And a friend of mine, Danny Mekonnen, who leads the Debo Ring, a cracking modern Ethio-groove ensemble based on the E Coast, happened to be friends with Ayalew through his father, and he introduced me. And, I literally cold-chosen, got his wife on the phone, and made my pitch, and I started there. About 8 years afterward, he finally invited me into his abode in Denver, and I went there with Cameron Schaefer from Vinyl Me, Please, the subscription services based in Denver, with open ears and an open mind, and we sat downward and met with Ayalew and listened to all of his music, and by the end of that meeting, it was obvious that Ayalew was set to trust me with his recorded life's piece of work.

On the process that took 10 years

Alapatt: I would go to Denver with Oh No's brother Madlib, he'southward a hip-hop producer that I'grand partners with, and I would become to Denver to do shows and I'd call Ayalew's married woman, Helen, and I said:

"Hey! Y'all know we're doing a show this Saturday, let'southward come up…" She was similar "Oh yeah, of grade, merely we have church, and so you'll have to come up very early in the morning".

Meanwhile, we're leaving the society at 4:00am, you lot know, and so I was like, that'south not going to work, but…oh yeah, just stay upwards, and and so show upwardly smelling like wine or something, that was not going to be a adept look, I could already tell.

Ayalew's a teetotaler, it turns out, and then I was wise to not just show up disheveled after running an event with Madlib. Just, when we did prove up, it was very meaningful, and information technology was very, how do I put this…it was obvious that Ayalew hadn't thought about this music in the same mode that we'd thought well-nigh it, because the outset questions we were asking him was most James Brown and Jimi Hendrix and Mulatu Astatke, and meanwhile he was talking about the entire lineage of his recorded career, much of which was done in underground, you know, upwardly until the point he had to go out Ethiopia, and some of which has been lost to time.

McDonnell: And then, 1 of the interesting things here is that Ayalew has washed a few gigs, he'southward gone out and played a couple times now, he'southward an older guy, but it sounds like he's still got a little urge to perform out at that place.

Alapatt: Oh absolutely, when we sabbatum down, Cameron Schaefer and I, at his house, and he had this very rare 7", the seven" that Oh No had sampled for that 1 rail that we put in the Mountain Dew commercial, which started the whole ball rolling; when he played that, he started singing along with it, and it was one of those moments that I was happy to take an iPhone, normally I like to keep it in my pocket, but information technology was so special, I had to record information technology because he was singing along with the tape and he sounded similar the record.

He's a little bit younger than his peers, like Alemayehu Eshete, Mahmoud Ahmed, Tilahun Gessesse; Ayalew must exist about 60-something now, and he'due south very sprite. And so, he's been performing, but he's not performed this music, and with the re-release that we did with Vinyl Me, Please, and, by the way, the only mode that you can become this music is on vinyl, if you're not streaming it…

On the vinyl revival

McDonnell: I'm all about the vinyl revival.

Alapatt: Yeah, me too, and Vinyl Me, Please is amazing because they accept a subscription service and they deliver it to subscribers, so with this Ayalew Mesfin record, they fabricated information technology their tape of the month, and they're delivering it to thousands of people that would never even know of seventies Ethiopian music, permit lone Ayalew Mesfin. And, they helped become these shows together; we're doing three shows with Ayalew and the Debo Ring, and the starting time one's boot-off in Denver with Madlib.

McDonnell: That's super cool. Now, how do you lot fit him into the remainder of your itemize? You've got and then many different kinds of music, but lots of it is seventies funk that people never heard, from Africa…

Alapatt: Well, I look at it this way, I came into all this stuff through hip-hop, and so at first I was looking at music from this era you lot know the late sixties, early seventies, up until the early on eighties, as source material for hip-hop producers, hip-hop DJs, and then I started realizing that what I really loved was the rhythmic revolution that people like James Brown and Miles Davis and Jimi Hendrix all honed in the nineteen sixties. So, in one case I started realizing where that went all around the world, I started realizing that there were tremendous similarities with all of these musicians, because that music exploded outwards at the same time that the influence was coming inwards from all of these dissimilar places. So, James Brown, for case, he toured all over Africa, and I don't think he toured Ethiopia, but it's obvious that Ayalew Mesfin was listening to James Brown. So, if I started my reissue career with the Kashmere Stage Band and Carleen and The Groovers, 2 contained funk ensembles from America that were influenced past James Brownish, and at present I'thousand issuing Ayalew Mesfin'southward music and it too was influenced by James Brown, well that's already a starting point that a person who's been listening to my reissues for the past xvi years can sink their teeth into, and, you know, of form, open their ears to.

On James Chocolate-brown's global influence

McDonnell: Information technology's funny, James Brown: his touch was so much more than than nosotros ever heard back for and so many years, but now we get to hear his true impact out there in the world.

Alapatt: Oh, I mean, and it's not the extravaganza that began with The Blues Brothers and, you lot know, reached its lowest point sometime in the late nineties. This is James Brown at his most peppery, when truly the earth over had to react to him in the same way that they had to react to The Beatles, and all different types of ethnicities and ages all had to admit the power of James Chocolate-brown and his bands. I hateful, his bands are very important, because his bands were as important as he was.

Zambian rock: Welcome to Zamrock!

Alapatt: The Zambian compilations were all centered around this style of music that contemporaneously past Zambians was termed "Zamrock", and this was music that was made after Zambia threw off the British colonial yoke nether its showtime president, Kenneth Kaunda, and really reached its acme in the early to tardily seventies. It was a tremendous moment for Zambian musicians who took to rock music, and a scrap of funk, just more often than not stone, more than any other African state that I can recall of at the fourth dimension, with the exception of mayhap Nigeria, and they took this stone music, largely influenced by American and European bands, and they made it uniquely Zambian. So, you lot hear Chrissy Zebby Tembo, in this case, although he's singing in English language, he's singing a song called "Born Blackness", and he's asking some very pertinent questions for a recently liberated state that was experiencing tremendous aggrandizement and myriad problems, from child starvation to the devaluation of its currency; it's telling, to me. And, when y'all mind to the other music he made with his Ngozi Family unit Band and Paul Ngozi, the leader, you hear them singing in the native languages of Zambia, and using native Zambian rhythms, and mixing it with stone music, and it became this really thrilling unique thing. I really wanted to tell the story of the entire scene, and that'due south what those two books and albums that accompany them hope to do.

McDonnell: Why practice you think, through the oddities of distribution, we all got to hear a lot of Fela in the seventies or eighties, but we never got to hear Zamrock?

Alapatt: Well, you lot know, I really idea about that because Fela, of course, was a large deal on the African continent, as well as exterior in the African Diaspora, and so, of course, from there, across. I started looking into the population numbers in a country like Republic of zambia and a country like Nigeria, and at Zamrock'southward height, which would probably be Fela's height too, just Lagos solitary had a larger population than the entirety of Republic of zambia. So, the idea of a Zambian record manufacture existing for Zambian musicians that were pressing and releasing music for Zambians in Republic of zambia, the chances of that spreading a little further than, let'due south but say Rhodesia or Botswana or Malawi, are very slim. Simply, the chances of a musician from Lagos, an oil rich part of Nigeria, being able to spread his music further, well, that was a little bit more obvious.

Nigerian rock: Wake Up You!

Alapatt: And, it's funny that yous were talking about Fela in the context of the Zamrock scene, considering he was an influence in that location, and of course in Ethiopia likewise. But, in Nigeria, Fela's music, and we make the statement in the Wake Up You! books, came to prominence largely in function of the Nigerian rock movement that happened after the end of the Biafran Civil War, and so his music eclipsed it, and led to that music'south demise.

McDonnell: This music sounds so fresh today, whereas a lot of music from the seventies or eighties or nineties, does not sound fresh. Why is that?

Alapatt: I hear you human, and I think that, when you hear, like on that Apostle'south rails, you hear that pulsate suspension that starts the beginning of the vocal, and it'southward obvious that it's a funk-rock pulsate pattern, merely it's just played in a totally different style, it's non like any of the classic breaks and beats that kind of inform the hip-hop generation, it'south a unlike thing, and it's also not the kind of Afrobeat groove that Fela was doing; this is a very unique audio, and I think that you can transpose that to all of the music that we're listening to. The Chrissy Zebby Tembo, that's kind of hard rock, proto-punk, but it has this really driving interesting beat that you can't really describe and you can't put in the context of the era in which it was recorded. Or, Ayalew Mesfin with that fuzz guitar leading off that "Hasabe" track, that was supposed to be a saxophone, and in nigh of Ethiopian music at the time information technology would have been, just there was Ayalew Mesfin deciding that he would transpose the saxophone to a fuzz guitar because he and his guitarist were into Jimi Hendrix, you know what I mean?

McDonnell: Yeah and I call back there'southward something about the rhythm being human being, it sounds similar somebody playing the drums, it does not audio like a drum car or something, and the guitarists audio like information technology was a existent improvisational moment, it doesn't sound like a expert moment.

Alapatt: Oh absolutely, I remember that the bulk of this music was made by the seat of your pants; fly into the studio, fly out. I mean, in Ethiopia, they were recording at the radio stations. In Zambia, they were recording wherever they could; they were recording at the mine studios that were used to produce tv set advertisements, you know what I mean? These were folks that got information technology together and recorded a tremendous amount of music in a very short amount of time, took reward of the window of opportunities that were open and afforded to them, and created these moments that seemed very human, because they were, and, I hateful, they're very emotional. That's the one thing that I want to say, all this music that nosotros're listening to is super emotional, y'all hear it in the way Chrissy Zebby Tembo sings that song, and most people in America are going to understand everything he'south maxim. The heartbreak is very real and he might take only gotten i take to do information technology.

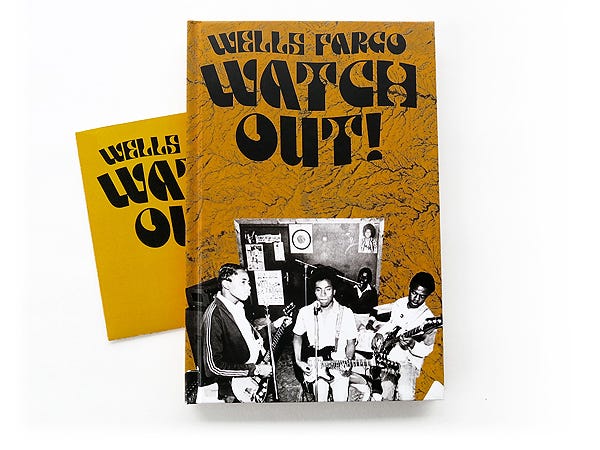

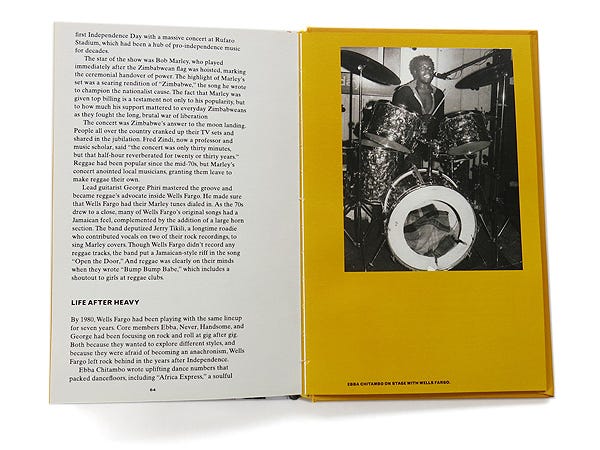

Zimbabwean stone: Watch Out!

McDonnell: Let's swing over to Zimbabwe for a 2nd. There was a grouping called Wells Fargo. I was trying to figure out the name of the ring, to proper noun itself after a kind of well known company, who were they?

Alapatt: Wells Fargo was a band that actually named themselves afterward a comic book that the band leader and drummer, Ebba Chitambo, had found, and he thought that it made sense considering the comic book was all about the Wild West in America, and he kind of saw his ring as a agglomeration of renegade outlaw types. And, although it isn't able to be easily discerned past get-go listening to their music, information technology was quite revolutionary. This was music that was used as the theme for the guerrilla insurgency that was beingness led by Black Zimbabweans against a minority led Rhodesian government, and their title song "Watch Out" was literally what many people would sing equally they were going into fight in these skirmishes and all-out battles. But, Wells Fargo too packed out agricultural fairs and they played clubs and they played for white Rhodesians and Black Rhodesians and dark-brown Rhodesians, and they simply believed in unity through music. And, Matthew Shechmeister, who is the partner that I did all the research into Zimbabwe with, and who catalyzed the whole matter by coming to me one mean solar day and saying "I know you lot know Zambian rock but practice you know Zimbabwean rock?", and I didn't; he made a tremendous attempt to explicate Wells Fargo's significance in a Zimbabwean sense, and I think he did a great job in the book that we put out.

McDonnell: What do y'all consider yourself? I'one thousand proverb you're Now-Again Records, and you're referring to the inquiry, and the books, and the everything. You're kind of a musical anthropologist or something?

Alapatt: You know, role of me wishes that I was, and part of me believes that I am. I mean, ultimately I wait at myself as just a record guy. I make records, I make new records, and I got into the music manufacture considering I wanted to put out new records. I put out a lot of records with people that I believe are some of the greatest living, or recently deceased, members of the hip-hop generation: Madlib, who, of form, is still my partner, J Dilla, who is no longer with us, MF DOOM, one of the greatest vocalists. And, I love doing that, and I still do that. But, a big part of my passion for that music, and the reason I was able to even encounter those people, is because I try my best to sincerely sympathise music from the past, and how information technology informs the music that nosotros're making correct at present. And so, when I tin can find a human thread that takes one story from 1 side of the world and brings it to another, and it tin can lead to an emotional moment with either i person or a bunch, well that'due south what I'm trying to detect. That'due south what I'grand honing in on, and that'southward what all this music represents to me. It's just one more than conversation in a much bigger discussion.

To listen to the full radio interview, click here.

Source: https://medium.com/wbezworldview/global-notes-now-again-records-f4a6d1cd1a27

0 Response to "Now and Again Records Eothen Alapatt"

Post a Comment